Disability in Costa Rica Operationalized as a Social Problem Points to Social Solutions

Erika Sanborne, University of Minnesota

Population Association of America PAA 2024 Annual Meeting, Columbus, OH US

April 17-20, 2024

Session 2: Health, Health Behaviors, and Healthcare

Welcome to study 2 of 3! Navigate via tabs. (TOC)

Study Overview

This poster in pdf format is hopefully in an accessible structure, ready to be read by a screenreader or similar tech.

However, if you are not sight-privileged, I recommend you scroll down and read the voiceover script at the next heading instead. It is structured for more fully accessible navigation.

I realize that, like most communication among researchers, the scientific poster format is inherently ableist, in this case by prioritizing the learning and participatory engagement of sighted scholars.

If anything here is not accessible to you, please let me know how I can help you.

View the original PAA poster pdf.

The following study overview is also a voiceover script of the poster.

And there is now some additional detail and context here on this website, which did not appear on the original, PAA 2024 poster. That is because this website is now serving a new purpose.

See also the complete Cartoon section for more.

Questions and Objective

- How do the results of analyses using a social model of disability differ from analyses using a medical model, when comparing national survey data?

- Are different well-being gaps apparent through the social model approach?

The objective is sustainable development, to begin bridging the gap between the conceptual framework that locates disability as the interaction between person and environment and the empirical demographic research that still treats disability as a personal, medical condition.

Background & Methods

Background

There is an increasing volume of research disaggregating demographic data by disability, as recommended by many*. Standardizing measurement is important for comparability. The Washington Group Short Set (WG-SS) is foundational for this. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development prioritizes leaving no one behind. Identifying and reducing within-country inequalities is key. Operationalizing disability as a personal problem suggests medical solutions. If disability is a social issue, accessibility is needed. This is worth investigating, as disability is an axis of inequality, and these deprivations are potentially so costly.

*United Nations (UN) Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD); UN Statistical Commission; World Health Organization (WHO); The World Bank; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)

See also the complete Background section for more.

Methods

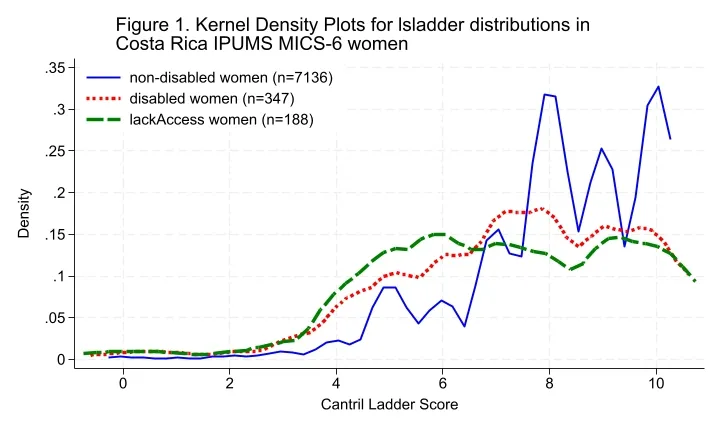

The regression models in this study (medical model and social model) examine the associations between life satisfaction (Cantril ladder) and disability within the theoretical framework largely established by the Washington Group. Life satisfaction serves as a comprehensive proxy for assessing individuals’ well-being, reflecting overall quality of life. Nationally-representative samples from Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Honduras, Cuba and Suriname were studied. Costa Rica models were fitted. (Data: IPUMS MICS)

Disability Indicators

Medical Model

Disability is functional impairment. The indicator of disabled in the present study is constructed from an IPUMS MICS survey item that asks whether respondents have difficulty seeing. If women reported at least “a lot of difficulty” seeing, they are disabled. This cutoff aligns with WG recommendations for comparability.

While there are additional survey items that measure functional impairment across more domains, this indicator is constrained to the domain of vision so that it is comparable to the social model which, due to data limitations, can only consider accessibility related to vision.

Social Model

Disability is lack of access. The indicator of lackAccess in the present study is constructed from two IPUMS MICS items. For women who reported specifically “a lot of difficulty” seeing and who also reported that they did not have eyeglasses, they lackAccess. Due to data limitations, this indicator does not span across other forms of access.

Regression Models

Outcome Measure

The outcome measure is the same in both models. It is the Cantril ladder IPUMS MICS survey item, an 11-level variable that is a standard measure of life satisfaction and a proxy for well-being. Consistent with OECD guidelines for comparability of well-being measures, respondents were shown an image of a ladder whose steps were numbered from 0 at the bottom to 10 at the top. Then they were asked to report the step at which they felt they were presently standing to indicate their level of life satisfaction.

Social Model

The social model here is an ordered logistic regression model. The social model predicts the probability of the outcome variable, a proxy for life satisfaction, being less than or equal to its various cutpoints on its 11-point scale, conditioned on several predictors, which include: ethnicity, wealth, education, marital status, perceived discrimination due to disability, age, or other, log-age, the interaction of ethnicity and lackAccess and, importantly the social model disability indicator, lackAccess, as previously defined.

-

Where j indexes the cutpoints of the 11-level ordered outcome variable Y, which is the Cantril ladder, life satisfaction measure,

logit(P(Y ≤ j)) = -

βj0 + β1 lackAccess + β2 ethnicity + β3 wealth

+ β4 edlevelwm + β5 married + β6 discriminated

+ β7 log(age) + βinteraction (lackAccess × ethnicity)

Medical Model

The medical model here is also an ordered logistic regression model. The medical model also predicts the probability of the same outcome variable being less than or equal to its various cutpoints on its 11-point scale, conditioned on several predictors. The medical model differs from the social model in two ways: the medical model does not include discrimination as a factor, and it includes the medical model disability indicator, disabled, as previously defined, rather than the social model disability indicator.

-

Where j indexes the cutpoints of the 11-level ordered outcome variable Y, which is the Cantril ladder, life satisfaction measure,

logit(P(Y ≤ j)) = -

βj0 + β1 disabled + β2 ethnicity + β3 wealth

+ β4 edlevelwm + β5 married + β6 log(age)

+ βinteraction (disabled × ethnicity)

See also the complete Stata Code section for more.

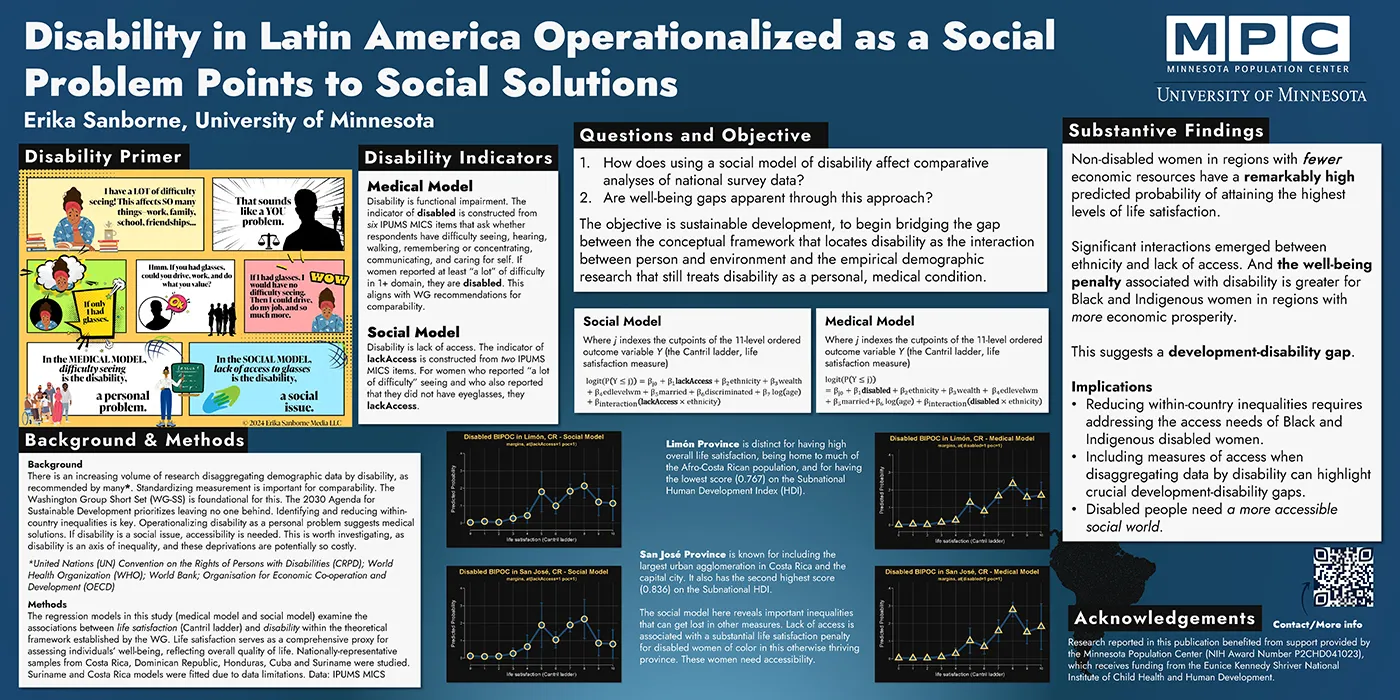

Poster Illustrations

- Limón Province is distinct for having high overall life satisfaction, being home to much of the Afro-Costa Rican population, and for having the lowest score (0.767) on the Subnational Human Development Index (HDI).

- San José Province is known for including the largest urban agglomeration in Costa Rica and the capital city. It also has the second highest score (0.836) on the Subnational HDI.

- The social model here reveals important inequalities that can get lost in other measures. Lack of access is associated with a substantial life satisfaction penalty for disabled women of color in this otherwise thriving province. These women need accessibility.

See also the complete Graphics section for more.

Substantive Findings

- Non-disabled women in regions with fewer economic resources have a remarkably high predicted probability of attaining the highest levels of life satisfaction.

- Significant interactions emerged between ethnicity and lack of access. And the well-being penalty associated with disability is greater for Black and Indigenous women in regions with more economic prosperity.

- This suggests a development-disability gap.

See also the complete Limitations section for more.

Implications

- Reducing within-country inequalities requires addressing the access needs of Black and Indigenous disabled women.

- Including measures of access when disaggregating data by disability can highlight crucial development-disability gaps.

- Disabled people need a more accessible social world.

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication benefited from support provided by the Minnesota Population Center (NIH Award Number P2CHD041023), which receives funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

The data used in this study are available courtesy of IPUMS MICS, University of Minnesota, www.ipums.org.

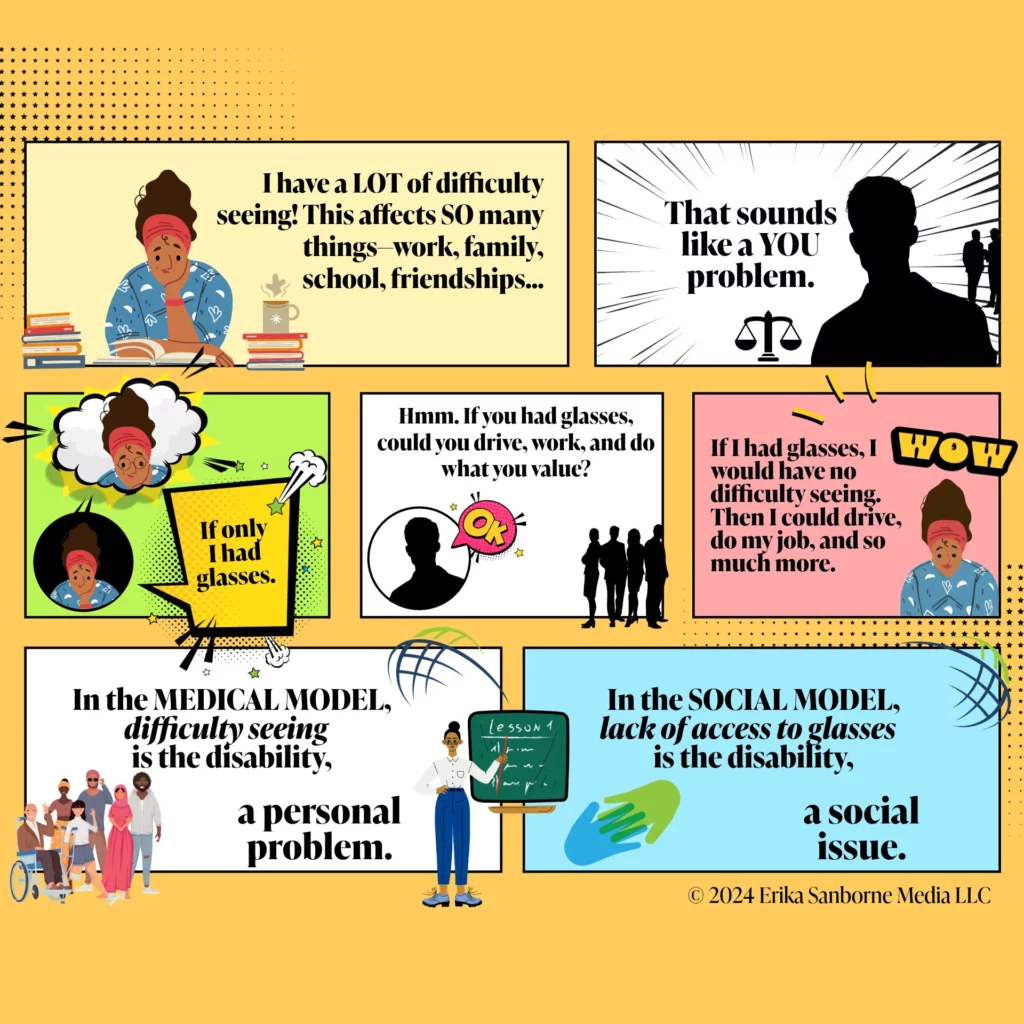

Cartoon

This cartoon explainer appears on the poster I shared at PAA 2024. It is near the top left, under the heading of Disability Primer. A descriptive transcriptive follows immediately below the graphic here which should be accessible to assistive technology.

This cartoon introduces two relevant IPUMS MICS variables (diffsee and glasses) used in the construction of the disability indicators that form the basis of the two regression models in the present study (medical model and social model). It also alludes to the capability approach, which is central to the theoretical framework of the present study, and it touches on how both accessibility and functional disability fit therein.

It does a lot for a cartoon. Including this on my poster made my research more memorable, easier to engage with for a wider audience (for potential networking across disciplines), and was generally more accessible, acknowledging the obvious exception that all poster sessions privilege the participation and presence of non-disabled people, most notably sighted people.

The inclusion of this cartoon explainer was a topic of discussion for several people who visited me at PAA 2024. Some take-aways included how it helped bridge the space between the research silos of potentially distinct fields, thus potentially fostering interdisciplinary collaboration. This also lets anyone have a quick understanding of key concepts and, with interest, a way to ask questions. It’s also more accessible to researchers with ADHD heedless of their familiarity with my work.

Descriptive transcript

This is a comic-style cartoon explainer with seven frames. There is one main character, Maria. She’s a woman with medium brown complexion, and lots of hair styled neatly and high above a headband.

frame 1: Maria is sitting at a desk with a stack of books, one open book, and a steaming beverage. She has a frustrated or sad facial expression. Maria says to herself, “I have a LOT of difficulty seeing! This affects SO many things – work, family, school, friendships…”

frame 2: A black and white silhouette of a man is shown standing tall in front of the scales of justice. He replies, “That sounds like a YOU problem.”

frame 3: Maria is musing, thinking to herself in a thought bubble, “If only I had glasses.”

frame 4: The silhouette man replies to Maria’s introspection, saying, “Okay. Hmm. If you had glasses, could you drive, work, and do what you value?”

frame 5: Maria replies to the silhouette man, “Wow. If I had glasses, I would have no difficulty seeing. Then I could drive, do my job, and so much more.”

Frames 6 and 7 are the teaching frames in summary. In between them is a teacher, pointing to a chalkboard, emphasizing that these two frames are instructive.

frame 6: There is a small group of disabled people off to the side. One person is sitting in a wheelchair, another person is missing a leg, a third is wearing dark sunglasses suggestive of being blind. The text overlay for frame 6 reads: “In the MEDICAL MODEL, difficulty seeing is the disability, a personal problem.” Difficulty seeing is in italics.

frame 7: Decorative graphics frame the text overlay for the last frame which reads: “In the SOCIAL MODEL, lack of access to glasses is the disability, a social issue.” Lack of access to glasses is in italics.

Background

This section covers two aspects of background information: a brief review of important points from prior relevant literature, and a bit of background on how the present study arose. And since the present study is the reader’s entry point, I will begin with what led into the present study of operationalizing disability.

In my previous study (to be detailed more thoroughly soon, like what you’re reading now) which I presented at PAA 2023, I was interested in how well-being, measured through life satisfaction, can potentially reorient national policy in terms of sustainable development. It was a deep dive into the predictors of subjective well-being, as measured through life satisfaction, consistent with OECD guidelines. The focus was on the well-being of women.

Highlights from that study included that while analyzing life satisfaction across all countries in the IPUMS MICS Round 6 dataset (n=513,744 women, in 29 national samples), Costa Rica emerged as an important case study for several reasons. Costa Rica had the #1 highest life satisfaction of all surveyed countries. Costa Rica had been touted by many (i.e. The World Bank, UN) as a “development success story” and, from what I could tell, it was that. Costa Rica also had the highest disability prevalence among women of all 29 surveyed countries.

One of the implications from that prior study is that sustainable development will require that things change to include (in the case of Costa Rica) disabled Afro-Costa Rican women, especially those living in Limón, since disability was highest specifically there. But there was something else that my first study suggested for further study.

I was led to investigate how it could be that the women in Limón who were not disabled had the highest life satisfaction of all women in Costa Rica, while the women in Limón who were disabled had the lowest life satisfaction.

To better understand these disparities, I focused on the social stress process (Dohrenwend 1978; Pearlin 1989). What are the exogenous variables, and what might be some of the stressors forming that multidimensional array? In particular, status strains and ambient strains seemed probable, the latter given that women in Limón are geographically set apart as compared to women in any other province.

Limón is a distinct subnational region of Costa Rica is several ways, including that the region has the fewest resources and most of the country’s Black/Afro-Costa Rican population.

And even though the women with the lowest life satisfaction were disabled (as measured in the first study in terms of functional impairment), and those with the highest life satisfaction were not disabled, they were all neighbors in Limón. To not consider a myriad assembling of factors would have been to risk potentially accepting a mere “proxy indicator of chronic hardship” (Pearlin 1989:245), which remains one of my favorite phrases.

I like that phrase because it gets at intersectionality (Crenshaw 1989) in the stressors, and the reality of multiple status strains, also important to understanding a situation. This holds at the subnational level in terms of the history of cohorts, and the accumulation of culture.

I suspect therein lies some of the joy that buoys the non-disabled women in Limón, because I have come to appreciate that there’s no place like it. While the women of Limón have this obvious potential vulnerability to the constellation of stressors, they also have this obvious access to a constellation of coping resources, just not the kind that’s needed when it comes to disability. That’s what I set out to better understand in the current study you are otherwise reading about on the present website.

According to the capability approach, well-being is evident through people’s freedom to be and to do the things that they have reason to value (Sen 1999). And whilst the economists will measure societal progress by utility, and their accounting takes the form of doing math and tallying resources, they cannot account for how the non-disabled women in Limón, the region with the least wealth and by far the fewest resources, are the happiest.

Disability does something. And if development is to be sustainable, countries must leave no one behind. The United Nations (UN) has Stakeholder groups – non-state actors who regularly engage with the UN to influence and contribute to its initiatives, policies, and decision-making processes. One of them is the Stakeholder Group of Persons with Disabilities.

Reading their position papers as submitted to the UN High Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development (HLPF) over the years has been instructive. While they contributed a 17-page paper in 2016, which had 26 footnotes and the endorsement of 312 Disabled Persons’ Organizations (DPOs) drawing from every region of the world, most recently in 2023, they submitted just over one page of text, no references and a clear but desperate-sounding plea for accessibility and inclusion.

“… we do not want to be left behind. Despite these (tasks and labors which this group has done towards sustainable development worldwide) persons with disabilities were largely left out of the national-level consultations. DPOs are looking for opportunities to work with governments, and many are being turned away. Public consultations often exclude persons with disabilities themselves and their representative organisations. Even when wider society is invited to participate, meetings and documents are not accessible for many persons with disabilities, thus excluding them from democratic processes…” (Stakeholder Group 2023:2).

Sustainable development must be disability inclusive development, and development is not sustainable if persons with disabilities are left behind. The UN and all UN member states have agreed that we must endeavor to leave no one behind, according to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

The 2030 Agenda is inclusive of persons with disabilities, and it aligns with the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) which was adopted in 2006 and sets international standards that promote the rights, dignity, and inclusion of people with disabilities (United Nations 2006).

Broadly, the CRPD is a major human rights treaty, the first to be ratified in this century, and one that reflects a major shift from considering disabled people as objects of medical intervention to subjects with human rights. Specifically, the CRPD encourages the collection and use of disability data to formulate and implement policies, thus helping to ensure that no one is left behind in a development context.

And so it is that the theoretical framework undergirding the present study is where the capability approach meets sustainable development for disabled women in Costa Rica. A brief overview of my methods, to include data, sample, construction of the indicators, operationalization, and statistical approach to modeling the outcome is addressed on the poster.

References

Bolgrien, Anna, Elizabeth Heger Boyle, Matthew Sobek and Miriam King. 2024. “IPUMS MICS Data Harmonization Code Version 1.1 [Stata Syntax].” IPUMS: Minneapolis, MN https://doi.org/10.18128/D082.V1.1.

Crenshaw, Kimberlé. 1989. “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics.” Pp. 139-66 in University of Chicago Legal Forum.

Dohrenwend, Barbara Snell. 1978. “Social Stress and Community Psychology.” American journal of community psychology 6(1):1-14. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00890095.

National Institute of Statistics and Censuses and UNICEF. 2018. “Costa Rica Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2011, 2018 [Dataset].” San José, Costa Rica: https://mics.unicef.org/.

OECD. 2013. OECD Guidelines on Measuring Subjective Well-Being: OECD Publishing.

Pearlin, Leonard I. 1989. “The Sociological Study of Stress.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 30(3):241. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2136956.

Sen, Amartya. 1999/2014. Development as Freedom. New York: Random House. UNICEF. 2019. “MICS6 Tools.” https://mics.unicef.org/tools#survey-design.

Stakeholder Group of Persons with Disabilities. 2023. “Position Paper.” Vol. New York: United Nations High-Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development (HLPF 2023).

United Nations. 2006. “Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and Optional Protocol.” https://social.desa.un.org/issues/disability/crpd/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities-crpd.

Descriptive Graphics

| Province & Ethnicity1 | n (disabled)2 | Proportion ‘disabled’ (as %) |

|---|---|---|

| Heredia – White residents (n = 182) | 14 | 7.7% |

| Heredia – People of Color (n = 232) | 10 | 4.4% |

| Limón – White residents (n = 431) | 34 | 7.9% |

| Limón – People of Color (n = 628) | 36 | 5.8% |

1 For brevity, Tables 1 through 5 summarize weighted means and frequencies for White residents and People of Color in Heredia and Limón, as the provinces with the most and the fewest resources respectively.

2 The ‘disabled’ indicator represents ‘a lot of difficulty’ seeing or ‘cannot see at all’. See also the complete Stata Code section for more.

Note 1. People of Color show a disproportionately lower rate of reportedly having ‘a lot of difficulty’ seeing or ‘cannot see at all’ as compared to White residents across provinces. White residents’ rate is similar in Heredia and Limón. These initial surprises may reflect measurement error, bias, differences in reporting, or something else. They are likely reflecting something other than an aspect of disability prevalence, because extant data affirm that disability prevalence is higher across the board for People of Color in Costa Rica. See also Table 6 for granularity.

| Province & Ethnicity1 | n (lackAccess)2 | Proportion ‘lackAccess’ (as %) |

|---|---|---|

| Heredia – White residents (n = 182) | 6 | 3.2% |

| Heredia – People of Color (n = 232) | 6 | 2.5% |

| Limón – White residents (n = 431) | 23 | 5.3% |

| Limón – People of Color (n = 628) | 22 | 3.4% |

1 For brevity, Tables 1 through 5 summarize weighted means and frequencies for White residents and People of Color in Heredia and Limón, as the provinces with the most and the fewest resources respectively.

2 The ‘lackAccess’ indicator combines having exactly ‘a lot of difficulty’ seeing with having no eyeglasses. See also the complete Stata Code section for more.

Note 2. Data limitations are apparent here, yet there is some preliminary information of use. Limón residents clearly lack access on this measure more than residents in provinces with more resources. Despite obvious data limitations, further inquiry is suggested to understand the role of accessibility. See also Table 7.

| Province & Ethnicity1 | n (‘discriminated’)2 | Proportion ‘discriminated’ (as %) |

|---|---|---|

| Heredia – White residents (n = 182) | 25 | 13.5% |

| Heredia – People of Color (n = 232) | 35 | 15.1% |

| Limón – White residents (n = 431) | 32 | 7.5% |

| Limón – People of Color (n = 628) | 56 | 8.9% |

1 For brevity, Tables 1 through 5 summarize weighted means and frequencies for White residents and People of Color in Heredia and Limón, as the provinces with the most and the fewest resources respectively.

2 The ‘discriminated’ indicator includes perceived discrimination on the basis of disability, age, or other reason only. See also the complete Stata Code section for more.

Note 3. Ethnicity does not seem to be a big factor in who reports perceived discrimination on the basis of disability, age, or other reason. Province does seem to matter a lot, with residents in Heredia reporting discrimination at much higher rates. This could reflect a reporting bias, in which Heredia residents are possibly more educated on their rights or perhaps feeling more empowered to assert them. Differences between provinces could reflect local culture. These differences could also be a matter of measurement error related to question order or something else.

| Province & Ethnicity1 | Less than primary (%) | Primary (%) | Secondary (%) | Tertiary / higher / university (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heredia – White residents (n = 182) | 0.16% | 11.55% | 30.73% | 57.56% |

| Heredia – People of Color (n = 232) | 0.57% | 10.09% | 46.81% | 42.53% |

| Limón – White residents (n = 431) | 2.22% | 29.06% | 51.90% | 16.82% |

| Limón – People of Color (n = 628) | 1.39% | 24.58% | 53.70% | 20.33% |

1 For brevity, Tables 1 through 5 summarize weighted means and frequencies for White residents and People of Color in Heredia and Limón, as the provinces with the most and the fewest resources respectively.

2 The ‘edlevelwm’ variable from IPUMS MICS is a 5-level ordinal measure of highest level of school attended by the woman. This sample had only 4 levels in all but one province. See also the complete Stata Code section for more.

Note 4. Both ethnicity and province factor separately and together towards highest level of school attended by the woman. This could be an additional outcome measure for modeling disability data as well. And this variable syncs with SDG 4 (Quality Education) and Targets 4.1, 4.3, and 4.5. If disabled women (by either operationalization) are left behind on this measure, that’s an important data story.

| Province & Ethnicity1 | n (‘wealth’)2 | Proportion ‘wealth’ (as %) |

|---|---|---|

| Heredia – White residents (n = 182) | 159 | 87.8% |

| Heredia – People of Color (n = 232) | 194 | 83.4% |

| Limón – White residents (n = 431) | 212 | 49.2% |

| Limón – People of Color (n = 628) | 278 | 44.3% |

1 For brevity, Tables 1 through 5 summarize weighted means and frequencies for White residents and People of Color in Heredia and Limón, as the provinces with the most and the fewest resources respectively.

2 The ‘wealth’ indicator represents anyone whose wealth index score is above zero. The wealth index itself is a standardized distribution (with a mean ~ 0 and a standard deviation ~ 1) intended to reflect the effects of wealth without directly measuring it, computing a wealth index score mostly by tallying ownership of household goods and basic services.

This household wealth estimation practice is based on the popular Filmer and Pritchett method of doing so. In this study, ‘wealth’ is 1 for all positive wealth index scores, which is approximately the 50% above the median for the country, given the normalized index from which it is constructed. See also the complete Stata Code section for more.

Note 5. Wealth varies in big ways by province and in small ways by ethnicity, and an interaction between province and ethnicity is likely here. Since a chi square test for independence cannot be done with survey data (although I could do so manually), relationships between ethnicity, province and ‘wealth’ could be interrogated via logistic regression, i.e.

(svy: logistic wealth i.geo1_cr##i.ethnicity)

Table 6: Proportion of ‘disabled’ by Province and Ethnicity

| Province | Ethnicity | ‘disabled’ Proportion (%) |

|---|---|---|

| San José | White | 36.95% |

| POC | 30.11% | |

| Alajuela | White | 20.05% |

| POC | 18.26% | |

| Cartago | White | 13.20% |

| POC | 9.56% | |

| Heredia | White | 10.65% |

| POC | 11.11% | |

| Guanacaste | White | 4.52% |

| POC | 9.31% | |

| Puntarenas | White | 7.16% |

| POC | 11.68% | |

| Limón | White | 7.47% |

| POC | 9.96% |

See also the complete Stata Code section for more.

Note 6. This table depicts the proportions of ‘disabled’ women stratified by ethnicity and province.

Table 7: Proportions of ‘lackAccess’ and ‘discriminated’ by Province and Ethnicity

| Province and Ethnicity – ‘discriminated’ | lackAccess – Proportion |

|---|---|

| San José White – No | 35.54% |

| San José White – Yes | 46.58% |

| San José POC – No | 29.28% |

| San José POC – Yes | 35.59% |

| Alajuela White – No | 20.41% |

| Alajuela White – Yes | 17.57% |

| Alajuela POC – No | 18.12% |

| Alajuela POC – Yes | 19.18% |

| Cartago White – No | 13.39% |

| Cartago White – Yes | 11.93% |

| Cartago POC – No | 9.74% |

| Cartago POC – Yes | 8.42% |

| Heredia White – No | 10.56% |

| Heredia White – Yes | 11.26% |

| Heredia POC – No | 10.88% |

| Heredia POC – Yes | 12.67% |

| Guanacaste White – No | 4.71% |

| Guanacaste White – Yes | 3.19% |

| Guanacaste POC – No | 9.44% |

| Guanacaste POC – Yes | 8.45% |

| Puntarenas White – No | 7.47% |

| Puntarenas White – Yes | 5.09% |

| Puntarenas POC – No | 12.09% |

| Puntarenas POC – Yes | 8.96% |

| Limón White – No | 7.93% |

| Limón White – Yes | 4.38% |

| Limón POC – No | 10.45% |

| Limón POC – Yes | 6.73% |

See also the complete Stata Code section for more.

Note 7. Here.

Predictive Graphics

Note. Even with the data limitations, it does seem that the different ways of operationalizing disability may reveal different things in terms of who’s left behind.

forthcoming

Limitations

While there is a compelling case to be made for Costa Rica as a case study, and for prioritizing women’s well-being, limitations range from the obvious to the less-so. Generalizability is limited. Without longitudinal data, I cannot investigate causal relationships or really interrogate changes in an aggregated outcome over time because these data are cross-sectional and those conclusions would not be justified.

Another limitation is using life satisfaction as a sole outcome measure. Much validation work has been done on this indicator of societal functioning, progress and well-being, and yet perhaps other things have led to the outcome as measured, unnamed factors, unaccounted for response bias.

Also, this present study, with two starkly different disability indicators, risks losing nuance of what it means to be disabled. While ethnicity can be an important factor, I reluctantly had to bin small (not-White) categories due to a lack of statistical power. In several aspects of this study there are limitations confounded by the small subgroup sizes of disabled women, which can also lead to estimation issues.

I also feel that there are some limitations to using the Washington Group (WG) disability items. They have evolved to be accepted as a sort of unequivocal gold standard for comparative data science with disability disaggregated data. They tout themselves as the social model variables proudly, but they still lean heavily towards “personal problem” rather than “social issue” and, in my opinion, the risk here is that our research, even while doing what’s recommended, could devolve into “counting crips” like so much medical research does. As one disabled researcher, I think this is something we should be talking about as well.

The social model does reach across more people by including perceived discrimination according to disability, age, or other reason, but it can only account for a lack of accessibility, the central point of this research, related to one domain of functional disability (vision). This limitation is inherent and due to data limitations. The hope is that upcoming surveys will continue to improve on their disability data practices, so as to begin narrowing the well-being and development gaps observed by disability.

As the graphics on the PAA 2024 poster or elsewhere on this webpage depict, the well-being (Cantril Ladder) gaps that are evident when using the social model versus when using a medical model are more of a minor translation than a major shift. This is due to their shared, convergent validity and also the data limitations (only considering vision and glasses).

But when we are considering the lives of people who are already multiply disadvantaged, a model that somewhat captures that additional burden of inaccessibility may be a better fitted model to predict life satisfaction.

Implications for subsequent research include exploring this matter of convergent validity more fully, testing better disability survey questions that give disabled people a chance to report something of the accessibility of their social world rather than just their diagnoses and functional impairments, which are their personal problems.

As accessibility is a social issue, its provision necessary for sustainable development, better answers to better questions might even lead to more relevant data stories being shared in national and international policy briefs. If disabled people are to be not left behind, we’re going to have to ask them what their access needs are.

Stata Code

Loading Data

/*****************************************************

LOADING THE IPUMS MICS WM + HH DATA

******************************************************/

/*

See also: https://mics.ipums.org/

I created an extract at mics.ipums.org after registering as a data user.

I downloaded from the women's samples, MICS Round 6, all available

samples, including all life satisfaction, disability, discrimination, and

ethnicity variables. In addition I included various demographic

and geographic variables and weights.

From the household samples, I downloaded ethnicity of head of

household to merge where not available for the women.

To construct the starting file, download the zip package from

IPUMS MICS and run the master mics_xxxx.do file.

After that runs, choose SAVE AS and name the file which BEGINS here

as mics_0004_wm.dta

*/

*************************************************************

/*

Merging ethnic* vars from Household Data in with with Women's Data

https://mics.unicef.org has "Guidelines for Merging Data Files of

a MICS Survey" - note that it is a Word doc about merging in SPSS

*/

*************************************************************

* Open the women data file

clear all

use "C:\Sync\Data\IPUMS-MICS\mics_0004_wm.dta" , clear

* Sort cases by ID variables.

sort cluster hhno linewm

* Save the women file.

save "C:\Sync\Data\IPUMS-MICS\mics_0004_wm-sort.dta", replace

* Open the household file.

clear all

use "C:\Sync\Data\IPUMS-MICS\mics_0004_hh.dta" , clear

* Sort cases by ID variables.

sort cluster hhno

* Save the household file.

save "C:\Sync\Data\IPUMS-MICS\mics_0004_hh-sort.dta", replace

* re-open the women's sorted file

clear all

use "C:\Sync\Data\IPUMS-MICS\mics_0004_wm-sort.dta", clear

* Merge household data onto the women using "many to one"

merge m:1 sample cluster hhno using ///

"C:\Sync\Data\IPUMS-MICS\mics_0004_hh-sort.dta", ///

keepusing (ethnic*)

* Save the merged women's file.

save "C:\Sync\Data\IPUMS-MICS\mics_0004merged.dta", replace

/**********************************************************

LOADING THE MERGED IPUMS MICS DATA

***********************************************************/

clear all

use "mics_0004merged.dta" , clear

*let's-a-go! Can now do cleaning data and creating indicators

Cleaning Data and Creating Indicators

/**********************************************************

CLEANING AND CREATING INDICATORS

***********************************************************/

* ssc install schemepack, replace

* ssc install coefplot, replace

* ssc install _GWTMEAN, replace

* ssc install elabel, replace

**********************

*** CLEANING ***

**********************

// recoding several vars DK (7) NR (8) and NIU (9) as missing

recode glasses diff* discrim* (7/9=.)

//recoding no response 98 and NIU 99 as missing

recode marst agewm edlevelwm (98/99=.)

recode ethnic_cr (98=.)

// recoding NR (8) and NIU (9) as missing; 98 and 99 in lsladder

recode lsladder (98/99=.)

rename lsladder ladder

recode ls* (8/9=.)

rename ladder lsladder

// recoding missing geo1_cr

recode geo1_cr (188998=.) //missing due to inc questionnaire

* Cleaning Costa Rica ethnicity of HH

/* In here, I'm gathering Chinese, Other ethnic group

not-specified, and None - no ethnic group together as Other/none.

Chinese people comprise 0.2% of the CR sample. Other non-spec

comprise 0.7% and None-no ethnicity comprises 7% of the CR sample.

And so my 3-to-1 'Other/none' ethnicity category is now comprised

of 88% who reported None-no ethnicity.

*/

gen ethbincr = ethnic_cr

replace ethbincr = 6 if inlist(ethnic_cr, 3, 7, 90)

replace ethbincr = 3 if ethnic_cr == 4

replace ethbincr = 4 if ethnic_cr == 5

replace ethbincr = 5 if ethnic_cr == 6

replace ethbincr = . if inlist(ethnic_cr, 98, 99) //missings

label define ethbincr 1 "Indigenous" 2 "Black/Afro-CR" ///

3 "Mestizo" 4 "Mulatto" 5 "White" 6 "Other/none"

label values ethbincr ethbincr

tab ethnic_cr ethbincr // inspect

* recoding missing ethnic_cr

recode ethnic_cr (98=.) //missing

* ethnicity

/* necessary due to small n counts in several regions by ethnicity,

and a need for statistical power; theoretically defensible in that

whiteness is likely what is most distinct in CR versus the differences

among the other ethnic groups

*/

/*

as an indicator of ethnicity, the categories of:

Indigenous,

Black/Afro-Costa Rican

Chinese

Mestizo

Mulatto

are included in 1, and White is 0 on this measure.

Other-not specified ethnicity, as well as None-no ethnicity

are recoded as missing (.) here.

*/

gen ethnicity= ethnic_cr

label variable ethnicity "ethnicity - POC Indicator"

recode ethnicity (1/5=1) (6=0) (7/99=.)

label define ethnicity 0 "White" 1 "POC"

label values ethnicity ethnicity

tab ethnic_cr ethnicity, missing //this verifies

*cleaning Costa Rica subnational regions and recoding

recode geo1_cr (188001=1 "San José") (188002=2 "Alajuela") ///

(188003=3 "Cartago") (188004=4 "Heredia") ///

(188005=5 "Guanacaste") (188006=6 "Puntarenas") ///

(188007=7 "Limón")

label values geo1_cr geo1_cr

tab geo1_cr

tab geo1_cr, nol

*logage

gen logage = log(agewm)

label variable logage "log-transformed age of woman"

//cleaning edlevelwm

recode edlevelwm (10 = 1) (20 = 2) (30 = 3) (41 = 4) (42 = 5)

label define edlevelwm 1 "Less than primary" 2 "Primary" ///

3 "Lower secondary" 4 "Secondary" 5 "Tertiary / higher / university"

label values edlevelwm edlevelwm

tab edlevelwm, nol

tab edlevelwm

**********************

*** INDICATORS ***

**********************

* create 'lackAccess' - the social model disability indicator

gen lackAccess = (glasses == 0 & diffsee == 3)

replace lackAccess = 0 if missing(lackAccess)

label variable lackAccess "Lacks Access - Vision (A lot)"

label define lackAccess 0 "No" 1 "Yes"

label values lackAccess lackAccess

tab lackAccess

/* Explainer/demo for lackAccess:

This will create the lackAccess indicator, a proxy for lack of access,

representing people who have a lot of difficulty seeing, yet no glasses.

Everyone who has 'no difficulty' seeing, or only 'some' difficulty, as well

as everyone who cannot see at all, and all those who have glasses, are

zero on this indicator, which is only indicated for those with

a lot of difficulty seeing + no glasses.

*/

*haveAccess, yes glasses + no difficulty

gen haveAccess = (glasses == 1 & diffsee == 1)

*note that respondents were asked to answer about their difficulty

*seeing while wearing glasses if they had glasses

replace haveAccess = 0 if missing(haveAccess)

label variable haveAccess "Has Access - Vision"

label define haveAccess 0 "No" 1 "Yes"

label values haveAccess haveAccess

tab haveAccess

* create 'disabled' - the medical model disability indicator

gen disabled = 0

replace disabled = 1 if diffsee==3 | diffsee==4

label define disabled 0 "not disabled" 1 "disabled"

label values disabled disabled

tab diffsee disabled //verify

/* From this construction, the indicator of 'disabled' includes

respondents with at least 'a lot' of difficulty seeing.

*/

*generating disabled_any

local diffvars ///

"diffsee diffhear diffwalk diffremcon diffcare diffcom"

gen disabled_any = 0

foreach var of local diffvars {

replace disabled_any = 1 if inlist(`var', 3, 4)

}

label variable disabled_any "Disability Indicator"

label define disabled_any 0 "Not Disabled" 1 "Disabled"

label values disabled_any disabled_any

tab disabled_any

/* Explainer/demo for disabled_any:

How to efficiently create a binary indicator based on the

presence or absence of functional disability across six domains

that are ordinal measures

This loop iterates over the list of disability variables, setting

the new 'disabled_any' variable to 1 if any of the disability

variables are 3 or 4, which represents at least "a lot" for

level of difficulty in that functional domain, thus moving

this disability Indicator 'disabled_any' to 1.

Else, 'disabled_any' stays at zero.

This construction is consistent with the WG recommendations

for disability disaggregated data, the basis for the MICS and

other survey tools that include these items, using 'a lot' as

the cut-off, thought to be roughly 'severe' disability on

scales that use that. 'disability_any' is the recommended indicator construction.

* creating binary indicator for positive wealth index score (wscore)

gen wealth = (wscore > 0)

label variable wealth "wscore indicator"

label define wealth_lbl 0 "negative wscore" 1 "positive wscore"

label values wealth wealth_lbl

tab wealth

*creating discrimination

local discrimvars "discrimgender discrimsexorien discrimage ///

discrimrelig discrimdis discrimother"

gen discrimination = 0

foreach var of local discrimvars {

replace discrimination = 1 if `var' == 1

}

label variable discrimination "Discrimination Indicator"

label define discrimination 0 "No Discrimination" 1 "Discrimination"

label values discrimination discrimination

tab discrimination

//explaining 'discrimination'

/* From this construction, the indicator of "discrimination" includes respondents

who responded "yes" to at least one of the 7 surveyed types of discrimination:

gender, sexual orientation, age, religion, disability, ethnicity/immigration,

or other reason. In cleaning, I recoded "don't know" to missing, and kept only

yes/no responses for analysis.

*/

*discriminated

* indicates discrimination in according to disability, age, or other

gen discriminated = (discrimdis == 1 | discrimage == 1 | discrimother == 1)

label variable discriminated "Social Model Discrimination Indicator"

label define discriminated 0 "No" 1 "Yes"

label values discriminated discriminated

tab discriminated //inspect

/* After reviewing the diff* variables' distributions, I note they are very

heavy with zeroes and most responses that are not 'no difficulty'

report only 'some' difficulty*/

*Creating binary indicators for each of the 6 functioning vars.

/*Here I do this by using a loop to iterate over each of the diff* vars and

generating a binary indicator for each one, naming it varnameyn. Then it kinda

collapses values of any impairment together and labels the values.

*/

local diffvars "diffcare diffcom diffremcon diffwalk diffhear diffsee"

foreach diff of local diffvars {

gen `diff'yn = `diff'

label variable `diff'yn "Difficulty `: subinstr local diff "diff" ""' Y/N"

recode `diff'yn (1=0) (2/4=1)

label define `diff'yn 0 "No Difficulty" 1 "Difficulty"

label values `diff'yn `diff'yn

}

tab diffsee diffseeyn //check it

*creating the 'a lot' indicators

local diffvars "diffcare diffcom diffremcon diffwalk diffhear diffsee"

foreach var of local diffvars {

gen `var'alot = `var'

label variable `var'alot "A lot of Difficulty `: subinstr local var "a lot of diff" ""' Y/N"

recode `var'alot (1=0) (3=1) (2=0) (4=0)

label define `var'alot 0 "None, Some, or Complete Diff" 1 "A lot of Diff"

label values `var'alot `var'alot

}

tab diffsee diffseealot // verify them such as

*create a binary indicator for marital status

// marst is 10=currently married, 20=formerly married, 30=never married

gen married = marst == 10

label var married "Married indicator"

label define married 0 "Not partnered" 1 "Married/in union"

label values married married

tab married marst // Verify

* Generating a Latin America indicator, comprised of UN

* World Regions: Central + South America, and Caribbean

gen latinam = inlist(regionw, 21, 22, 24)

label variable latinam "Latin America Indicator"

label define latinam 0 "not Latin Amer" 1 "Latin Amer"

label values latinam latinam

tab regionw latinam // verifies

*create an indicator for Costa Rica

gen CR = (country == 188)

label variable CR "Costa Rica Indicator"

label define cr_labels 0 "No" 1 "Yes"

label values CR cr_labels

tab CR //verify

* Creating indicator variables for each subnational region in CR

foreach i in 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 {

gen CR`i' = (geo1_cr == `i')

}

local regionNames ///

"SanJose Alajuela Cartago Heredia Guanacaste Puntarenas Limon"

foreach i in 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 {

local name : word `i' of `regionNames'

label var CR`i' "`name'"

label define CR`i'_lbl 0 "No" 1 "Yes"

label values CR`i' CR`i'_lbl

}

*drop all cases that are not in Latin America

keep if latinam == 1

/**********************************************************

Mario Flag Save Checkpoint

**********************************************************/

save "mics_0004-IP.dta", replace

program savecompressed

version 11.2

syntax [ , REPLACE ]

* Check if changes have been made to the dataset and if replacing

if "`replace'" != "replace" & c(changed) {

error 4 "Changes were made to the dataset. Use 'replace' option ///

to overwrite."

}

* Record the current memory size before compression

local width = c(width)

compress

* Save if dataset is now smaller and if 'replace' was specified

if "`replace'" == "replace" & c(width) < `width' {

save "`1'", replace

}

end

save "ipums_mics_2024-latinam-clean", replaceDescriptives

/*****************************************************

Let's-a-go!

*****************************************************/

clear all

use "ipums_mics_2024-latinam-clean" , clear

/* IPUMS MICS women's sample weight is weightwm;

it is the inverse of the probability of inclusion

- psu = cluster in this survey

- centered is a choice re: handling single PSU in stratum;

*/

svyset [pweight=weightwm], ///

psu(cluster) strata(stratum) singleunit(centered)

/*

Study population and sampling designs

The sampling units were women aged 15-49.

MICS uses a stratified, two-stage clustering design.

Other surveys that were used for validity checks:

The DHS program uses a two-stage stratified sampling design.

GWP uses a stratified random sampling design.

*/

* starting point with this study's survey design:

svydescribe

/*

From the above, I note there are 32 strata with 2-93

units in each, for a total of 140 clusters or PSUs.

How many observations are there per cluster or PSU?

Minimum of 1, mean of 15.3, maximum of 34

Observations in this design are female respondents.

And the degrees of freedom for this design would thus be

140 - 34 = 106 design df (n-PSUs minus n-strata). This

basically represents the number of independent pieces

of information available for estimating variances.

*/

/*****************************************************

DESCRIPTIVES

******************************************************/

* here is the list of variables used in this study

codebook disabled disabled_any lackAccess ethnicity ///

wealth edlevelwm married agewm logage discriminated ///

diffsee glasses round year CR* geo1_cr ///

weightwm cluster stratum psu, compact

* Who lacks access? Who is disabled?

* Who has a lot of difficulty seeing + no glasses?

* Who is disabled with 'a lot of difficulty' seeing?

svy, subpop(ethnicity): mean ///

lackAccess disabled ///

discriminated edlevelwm wealth, ///

over(geo1_cr)

*interrogating

estat size

* Descriptives for - key variables - weighted

* frequencies across binary ethnicity in

* Heredia and Limón, the Provinces w/most

* and least wealth

* Table 1

//disabled - weighted frequencies and CIs -

* Heredia - White

svy, subpop(if ethnicity == 0 & geo1_cr == 4): tabulate disabled, ci

* Heredia - POC

svy, subpop(if ethnicity == 1 & geo1_cr == 4): tabulate disabled, ci

* Limón - White

svy, subpop(if ethnicity == 0 & geo1_cr == 7): tabulate disabled, ci

* Limón - POC

svy, subpop(if ethnicity == 1 & geo1_cr == 7): tabulate disabled, ci

* Table 2

//lackAccess - weighted frequencies and CIs

* Heredia - White

svy, subpop(if ethnicity == 0 & geo1_cr == 4): tabulate lackAccess, ci

* Heredia - POC

svy, subpop(if ethnicity == 1 & geo1_cr == 4): tabulate lackAccess, ci

* Limón - White

svy, subpop(if ethnicity == 0 & geo1_cr == 7): tabulate lackAccess, ci

* Limón - POC

svy, subpop(if ethnicity == 1 & geo1_cr == 7): tabulate lackAccess, ci

* Table 3

//discriminated - weighted frequencies and CIs

* Heredia - White

svy, subpop(if ethnicity == 0 & geo1_cr == 4): tabulate discriminated, ci

* Heredia - POC

svy, subpop(if ethnicity == 1 & geo1_cr == 4): tabulate discriminated, ci

* Limón - White

svy, subpop(if ethnicity == 0 & geo1_cr == 7): tabulate discriminated, ci

* Limón - POC

svy, subpop(if ethnicity == 1 & geo1_cr == 7): tabulate discriminated, ci

* Table 4

//edlevelwm - weighted frequencies and CIs

* Heredia - White

svy, subpop(if ethnicity == 0 & geo1_cr == 4): tabulate edlevelwm, ci

* Heredia - POC

svy, subpop(if ethnicity == 1 & geo1_cr == 4): tabulate edlevelwm, ci

* Limón - White

svy, subpop(if ethnicity == 0 & geo1_cr == 7): tabulate edlevelwm, ci

* Limón - POC

svy, subpop(if ethnicity == 1 & geo1_cr == 7): tabulate edlevelwm, ci

* Table 5

//wealth - weighted frequencies and CIs

* Heredia - White

svy, subpop(if ethnicity == 0 & geo1_cr == 4): tabulate wealth, ci

* Heredia - POC

svy, subpop(if ethnicity == 1 & geo1_cr == 4): tabulate wealth, ci

* Limón - White

svy, subpop(if ethnicity == 0 & geo1_cr == 7): tabulate wealth, ci

* Limón - POC

svy, subpop(if ethnicity == 1 & geo1_cr == 7): tabulate wealth, ci

* or to just see edlevelwm by province, this is a nice table

svy: mean edlevelwm, over(geo1_cr)

*Table 6

// 'disabled' **************************************

svyset [pweight=weightwm], ///

psu(cluster) strata(stratum) singleunit(centered)

svy, subpop(CR): tab geo1_cr disabled, ///

count cellwidth(12) format(%12.2g)

svy, subpop(CR): proportion geo1_cr disabled, ///

over(ethnicity)

*Table 7

//'lackAccess' and 'discriminated' ******************

svyset [pweight=weightwm], ///

psu(cluster) strata(stratum) singleunit(centered)

svy, subpop(CR): tab geo1_cr lackAccess, ///

count cellwidth(12) format(%12.2g)

svy, subpop(CR): proportion geo1_cr lackAccess, ///

over(ethnicity discriminated)

*visualizing the outcome measure's distribution (lsladder)

kdensity lsladder if countrylong==188 [aweight=weightwm], ///

kernel( epanechnikov ) name(CR_lsladder, replace) ///

title("Costa Rica MICS6 women's lsladder (n=7483)")

/* kernel density plot is a probability density function of lsladder.

The height of the curve at any point along the x-axis indicates the relative

likelihood of observing a given value of lsladder in that data, with the area

under the entire curve summing up to 1.

*/

Analysis

/******************************************************

ANALYSIS

******************************************************/

clear all

use "ipums_mics_2024-latinam-clean" , clear

svyset [pweight=weightwm], ///

psu(cluster) strata(stratum) singleunit(centered)

* kernel density plots for each of the three things:

* all women, 'disabled' and 'lackAccess'

kdensity lsladder if countrylong==188 & disabled==0 [aweight=weightwm], ///

kernel( epanechnikov ) generate(density_all x_all) ///

name(CR_lsladder, replace) ///

title("Costa Rica MICS6 women's lsladder (n=7136)")

kdensity lsladder if countrylong==188 & disabled==1 [aweight=weightwm], ///

kernel( epanechnikov ) generate(density_dis x_dis) ///

name(CRdis_lsladder, replace) ///

title("Costa Rica MICS6 women's disabled lsladder (n=347)")

kdensity lsladder if countrylong==188 & lackAccess==1 [aweight=weightwm], ///

kernel( epanechnikov ) generate(density_lack x_lack) ///

name(CRlack_lsladder, replace) ///

title("Costa Rica MICS6 women's lackAccess lsladder (n=188)")

* then I want to overlay them (note the generated density estimates

* and lsladder scores from before)

* Plot the three on a combined graph

twoway (line x_all density_all, lcolor(blue) lwidth(medthick) lpattern(solid)) ///

(line x_dis density_dis, lcolor(red) lwidth(thick) lpattern(shortdash)) ///

(line x_lack density_lack, lcolor(green) lwidth(thick) lpattern(longdash)), ///

legend(order(1 "non-disabled women (n=7136)" ///

2 "disabled women (n=347)" 3 "lackAccess women (n=188)") ///

position(10) region(color(white)) ring(0)) ///

title("Figure 1. Kernel Density Plots for lsladder distributions in" ///

"Costa Rica IPUMS MICS-6 women", justification(left) span size(*.9)) ///

ytitle("Density") xtitle("Cantril Ladder Score") ///

xlabel(#5, grid) ylabel(#10, grid) ///

name(CombinedKDensities, replace)

// this all exists offline - coming here soon